Where’s World?

A look at Greylock's history curriculum

November 18, 2018

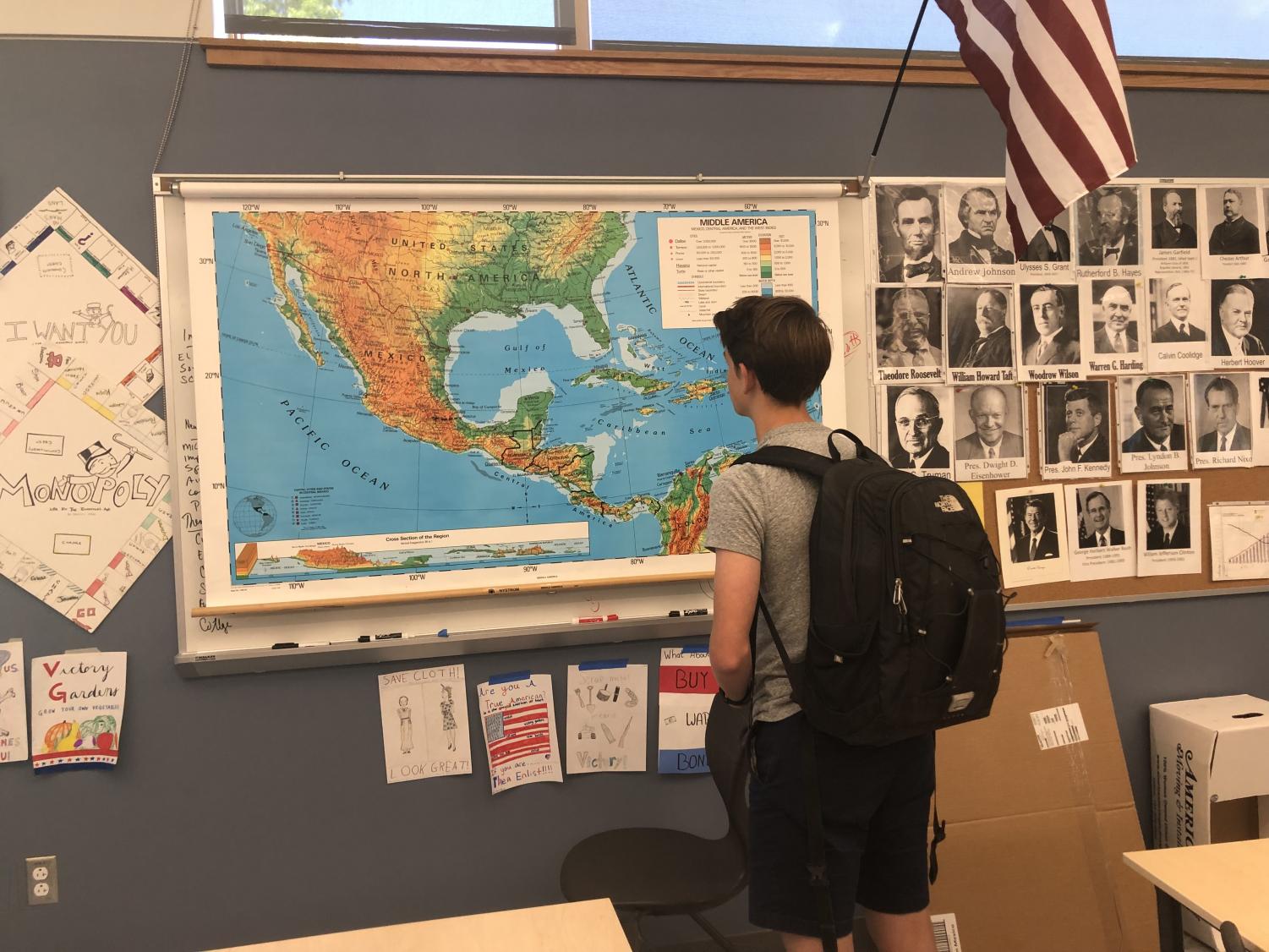

Greylock students study physics. They study geometry, trigonometry, and biology. They read Lord of the Flies and To Kill a Mockingbird. They conjugate verbs. And they learn United States history.

The curriculum is broad, but one thing is missing, some students say: a thorough instruction of the history of the world.

“We learn a lot,” said one student. “But that’s not enough.”

This past summer, students, teachers, and parents made many attacks toward the College Board. Perhaps the most significant of these attacks did not concern the highly controversial SAT or the “not-for-profit” company’s business model as they usually do, but the Advanced Placement World History Curriculum. In June, the College Board announced that the scope of this curriculum, which previously covered over ten thousand years of history, would start in 1450 for the 2019-2020 school year.

Teachers were not happy. Throughout the month, they protested against the elimination of what they saw as countless events crucial to a full understanding of world history. At a public forum in Utah, several of these teachers were given the opportunity to express their concerns regarding the curriculum to Trevor Packer, director of the AP program. One protester was Amanda DoAmaral, who had previously taught history but was unable to continue as a result of a lack of pay. DoAmaral told Packer that providing a full scope of World History would “[show] our black and brown and our Native students that their histories matter, their histories don’t start at slavery. Their histories don’t start at colonization. You’re just another person of authority telling my students that they don’t matter, and you need to take responsibility for that.” Starting at the rise of the major European powers in the fifteenth century, claimed DoAmaral, would put the West at the center of history instruction.

In response to these protests, College Board pushed the start date of the curriculum back to 1200 – an extra 250 years for students to understand the development of non-Western cultures. Many teachers were grateful, but many were unimpressed. Valerie Strauss of the Washington Post pointed out after the amendment that many of the crucial events that protesters were angry about losing would still be missed or brushed over. Important events referenced by a Change.org petition against the initial change included creation of the first civilizations and development of classical empires. Even starting at 1200, these phenomena would not be covered sufficiently.

It is against this backdrop of curriculum-based controversy in conjunction with modern-day political and social divides that a look at Mt. Greylock’s history curriculum is compelling. As teachers across the nation protest against the changes in the AP World History curriculum, students at Mt. Greylock are not able to take the course at all.

The current school year is Mt. Greylock’s second year in a new curriculum – one that does not focus on survey-based world history instruction but instead features semester-long thematic courses, including “Migration and Movement” and “Subject to Citizen,” that zoom in on specific historical trends and their significances. History teacher Andrew Gibson said that the department and administration decided to make the change largely because “more intense learning will happen when you dig deep into a specific area.” However, Gibson personally advocated for survey-based instruction when the curriculum changes were being debated, as “if you have students who are completely ignorant of huge swaths of world history, you have to start somewhere. What I liked about the survey is that it laid down a basic foundation – or mudsill, if you like – for students to continue to learn about these countries, peoples and stories.”

While many of the new thematic courses do focus on world history, many Greylock students will not ever take them. At the end of the day, both survey-based world history instruction and the thematic courses that are currently offered provide students with more world history than no world history. As history teacher Thomas Ostheimer pointed out, a large number of students go down the AP route. This entails taking the required freshman American History II course (or “America in the World”), followed by AP European History in sophomore year, AP US History in junior year, and often Ostheimer’s AP Psychology course in senior year. Psychology has evolved into a substitute for history among seniors and some juniors, according to Ostheimer, as evident in the two large sections of AP Psychology in addition to one of Honors Psychology.

Mt. Greylock is the home of many extremely motivated students who would like to pursue every AP class that they can. Taking these three AP courses allows them to do this and gain the half of a point GPA boost that comes with AP. Again, one thing remains missing from this sequence: world history.

Jeffrey Welch, another history teacher at Greylock, told the Echo that “The AP offerings predate my tenure here, however World History is a relatively new offering from the AP; one which, with the current schedule and course offerings, we haven’t seriously debated offering.”

Nevertheless, many students argue that an AP World History course would be a welcome addition to the Greylock history curriculum. “I think that AP World should be offered, because why do other schools have it and we don’t?” asked senior Grace Miller.

Fellow senior Katrina Hotaling agreed. “If we’re going to offer [European History] and [US history] then we should definitely offer World too,” she said.

“I think you need to have to take a world history course before anything else,” argued junior Alex Morin. “If you don’t have any understanding of the world, how can you understand European or American or whatever other history you’re taking?”

Some students complained about the Western focus of the “AP Track.” Referencing the Euro-APUSH-Psychology sequence that many high schoolers elect to take, one student said that “none of [the curriculum] widens your worldview to other countries that you aren’t necessarily familiar with.” Some students who are on this “AP Track” will go through a few years of vigorous study of history but they will not be exposed to crucial information.

“I don’t know if I can even form an opinion because I know so little about what I’m missing out on,” junior Charlotte Rauscher pointed out. “I’ve enjoyed the history classes that I’ve taken here, but is there more? Probably. Should I know more? Probably? Do I know enough? Probably not.”

If a student attends middle school at Greylock and decides to take AP US History at some point, they will have taken three years of United States history by the time they graduate.

“While [US history] might help cultivate good national citizens, it doesn’t help to create good global citizens necessarily,” said junior Jimmy Brannan. According to Brannan, being a global citizen is important because “it’s one planet – we all share it.” Junior Nicole Overbaugh suggested an integration of other countries’ histories into Western-focused classes like AP European History and AP US history, claiming that it “would be beneficial to all of us, as we would gain a broader understanding of the world.”

AP World History teachers at other schools in the county claim that the content is crucial. The Echo reached out to Matthew Webster, a history teacher at Taconic High School, who said that “as members of a democratic society, there is a need for informed viewpoints to make rational and just decisions,” and that “world history courses support that.”

Michael Sheehan, the AP World History teacher at Pittsfield High School, claimed to see similar benefits, explaining that at the time of course selection, “[members of the PHS history department] were drawn to AP World’s appeal of having a curriculum that was truly global in scope that provides an equal amount of content from all world regions. No more of Africa and Asia getting only the sad colonial story of the 19th and 20th centuries. We felt this was truly an important course to help make PHS students good global citizens.”

This last idea – the development of global citizens – is one that came up frequently in student conversation regarding history curricula. Many Greylock students, when asked, recognized the importance of being a global citizen, which was defined by Bianca Mariel of Voices of Youth as “an idea or person that inherit a sense of belonging to a community of human beings, regardless of specific identities.” However, senior Josh Cheung argued that global citizenship shouldn’t be the first priority.

The proportion of students who have taken world history in high school is rising. But at Mt. Greylock, that number is still low.

“The first objective of any country and its education department is to educate that person to be a successful citizen in that country first, and then from there you can branch off to the world,” claimed Cheung. “I think it’s important for Americans to understand American history and American politics first.” According to Cheung, what does need more emphasis is civics and politics, as “many people in this country aren’t educated… in how our government actually works, how they need to vote, and how a citizen should vote in a democracy.”

In this sense, the relative importance of global citizenship may be seen through the lens of prioritization: if national unity is a higher stake, than national citizenship may trump global citizenship as something to be looking for in history curricula.

“There might even be more division within out country than there is internationally,” noted junior Brandon Fahlenkamp. According to Cheung and Fahlenkamp, world history’s place in the back seat may have its own purpose.

Some students argued that national unity and global unity may not be as distinct goals as they seem to be. “It’s important to look inward, but our one country contains bits and pieces of cultures from all over the world,” commented junior Noah Greenfield. “In a sense, you can’t be acknowledging the existence of a national identity without that of a global one.”

The Greylock history curriculum might help students become global citizens in other ways. Welch explained that “I always seek to incorporate contemporary and local examples, to demonstrate that history happened here and that history often reverberates throughout the global community.”

But many students stressed that bits and pieces aren’t always enough. Overbaugh wants this integration of other countries’ histories and cultures to be a much larger part of the curriculum, and one student noted that while in AP history classes there are often end-of-year units on foreign cultures, “world history pushed after the AP exam” cannot substitute full courses.

Considering that the lack of world history arises primarily on the AP Track, dependence on AP courses could also be a root of the problem. Senior Josie Dalsin said that “I don’t really like the focus on the AP History classes. I really think it’s important that everyone can be exposed to different kinds of history without having to be afraid of the AP exam at the end of the year.” According to Dalsin, less focus on AP’s could welcome students to take classes regarding “how to be a global citizen,” as opposed to just the AP courses.

Elyse Wallash, a student at the West Valley College Global Citizenship Center, claimed in a 2014 paper that “global citizenship is having and acting on an additional feeling of connectedness that encourages people to think globally, and allows them to diversify and expand their communities.” Whether or not this sentiment is important or not is a matter of opinion. However, what is clear is that many Mt. Greylock students do not feel that they have been given this sense of connectedness by the classes that they take. Whether it is a problem having to do with the AP culture or with the course offerings, world history is not an integral part of a large portion of students’ educations. How this hole contributes to students’ places in a twenty-first century global society is, at the very least, something to be considered.