When Snow Melts and Waxes Burn

January 29, 2020

At the intersection of skiing, health, and climate: dirty chemicals, shrinking seasons, ardent activists, and less ardent leaders. The Echo talked to officials, high school and college athletes, coaches, and Olympians to learn more.

Berkshire Slush Fest

Berkshire Nordic Ski League director Joe Miller dubbed January 11’s race a “Nordic Slush Fest” before it even happened. When the athletes arrived at the course Saturday morning, they found a field of grass where the previous week’s start had been. A slew of last minute course changes had spectators trudging through a mile of ice to arrive at the 2-kilometer loop that had just enough powder to support the some 200 skiers in the league.

“We have less snow than we used to,” Greylock ski coach Hilary Greene said. “People begin to question why we’re even doing this, if we aren’t able to ski.”

For Greene, the community is looking at a new sport.

“Your sport that you know of as being cross-country skiing, where you go into the mountains and go for kilometers and kilometers, becomes reduced to skiing around a 1-k track,” she said. “You start to lose numbers.”

Research from the Climate Impact Lab predicts a significant drop in the number of skiable days over the course of the century. In a study titled “America’s Shrinking Ski Season,” authors Kelly McCusker and Hannah Hess predicted as much as 80 percent drops in the length of the season by late-century for some popular ski resorts if carbon emissions continue to rise. Oregon’s Mt. Bachelor, where the U.S. Cross-Country Ski team trains every year, may see a 23 week season turn to 12 weeks.

The research includes two projections: one for a continued rise in emissions, and one for the controlled emissions outlined in the Paris Climate Accords.

The rapid changes occur under McCusker and Hess’ “high emissions scenario.” The low emissions scenario projects a less but still significant decline in the length of the ski season. For Mt. Bachelor, it’s a 26 percent drop, compared to almost 50 percent under high emissions.

“It’s useful to look at two different scenarios,” Hess said, “to engage people in the exercise of imagining what the world could look like if we got serious about meeting our climate goals, versus what the world looks like if we don’t take the threat seriously.”

For the Berkshire League, this threat means an inconsistent race schedule and competitions scheduled just days in advance. None of the team’s races this season have occurred at their scheduled locations, and one has already had to be canceled.

“We’ve always had the ups and downs, but it’s a lot more severe now,” Lenox coach Joe Bazanno said. “Through the course of the year, week by week we don’t know what we’re doing.”

In an informal, small-scale survey of around 20 members of the Greylock ski team, all but one mentioned that they have noticed unreliable weather patterns over the course of their years on the team, with respondents mentioning that “there’s no snow anymore” and that “the league used to never have to cancel races, but now it’s completely normal.”

On the World Tour

Andy Newell has skied at the Olympics four times, giving him his fair share of snow. But he’s also watched the glaciers he’s trained on melt before his eyes.

When Olympic biathlete Maddie Phaneuf traveled to the Italian Alps to race, she expected to see powder. She found grass.

Noah Hoffman raced at Davos, Switzerland, on a course that had thrived with natural snow in the 1970s. He skied on “a ribbon of snow” through the woods.

Sam Shaheen’s memories of endless snow in middle school disappeared as he skied in a college league full of “artificial stuff.”

But Gian-Franco Casper, president of the International Ski Federation, hasn’t expressed much concern. “We still have snow, and sometimes even a lot,” he said.

The story for many professional skiers is the same. The snowy winters they experienced as younger athletes are faint memories. The culprit is climate change, and the responses range from activism to indifferency.

Those fighting back against McCusker and Hess’ high emissions scenario include Protect Our Winters, a nonprofit political action group advocating green legislation. The organization includes an athletic alliance, which has grown to represent nearly 100 athletes.

“POW has done a really great job of bringing together athletes who have the common experience of ‘oh god, something’s going on,’” said Simi Hamilton, three-time Olympic cross-country skier and member of the alliance. “It offers us a platform to share our experiences and share what we see throughout the year.”

While some organizations focus on encouraging environment-friendly personal practices, Protect Our Winters’ efforts center around broader changes in government policy and regulations. They make frequent visits to politicians’ offices. When President Donald Trump invited Olympic athletes to the White House, Maddie Phaneuf was instead representing the organization on Capitol Hill, talking to officials for the second time in her young career.

As an athlete who wants her sport to survive, Phaneuf said she wants to see political change.

“No matter how many U.S. citizens make our carbon footprint smaller, it’s not going to change the effects climate change is having on our planet that much,” Phaneuf said. “We need a systematic change. We need to be voting for people who are going to advocate for climate action.”

Ski resorts and organizations are also trying to hold onto their businesses as the dollars trickle away. In a 2018 study, Professor Elizabeth Burakowski identified a strong positive correlation between a year’s number of days with skiable conditions and amount of skier visits. Because the ski industry accounts for an annual $20 billion, a year with little snow can cost over 17,000 jobs and a billion dollars, the study found.

Last January, the National Ski Areas Association, the Outdoor Industries Association and Snowsports Industries America responded to this threat with the creation of the Outdoor Business Climate Partnership. The Partnership represents industry businesses, including resorts and retailers, in the political arena. Together, the three organizations account for 7.6 million jobs.

“When you speak as the collective voice of an $887 billion industry, it gives your message that much more power,” Adrienne Isaac of the National Ski Areas Association said. “There are so many members of Congress whose constituents rely on outdoor recreation for a vibrant local economy, to put food on their tables, or for their mental and physical health. Our members and our industry are directly impacted by the effects of climate change. It makes sense to band together to underscore the critical need for climate-smart policies at the federal level.”

The goals of the Partnership center around a rapid drop in carbon emissions and a transition to clean energy. In May, the new group traveled to Washington to push for a price on carbon. They are organizing another trip, Isaac said.

An Uphill Battle

But next to an array of athletes and businesses determined to fight climate change is an array of obstacles, including the International Olympic Committee and the International Ski Federation (FIS).

“FIS leadership is incompetent,” Olympian Noah Hoffman said. “President Gian-Franco Casper needs to leave. FIS is responsible for the health and well-being of all the skiing sports globally, and they are underperforming.”

Casper, who has now entered a third decade of leading the organization, got widespread criticism in February when he referred to “so-called” climate change.

“He’s just an old school Swiss guy who chain-smokes cigarettes and has no idea what’s going on outside of his little bubble,” Andy Newell said.

The International Ski Federation did not respond to multiple interview requests.

Newell also said the International Olympic Committee has made concerning decisions, notably in their choices of Olympic venues.

“The fact that the Olympics were held in Sochi seemed like a bonehead idea to me,” he said. “The IOC was so concerned with making big dollars and forming deals with Putin and the Russian government and satisfying all these different international sponsors that they agreed to hold an Olympic venue in a new area where they had to literally clear cut national forests to put in alpine ski areas, and they had to divert waterways to put in Olympic villages. So much environmental destruction, just for the sake of making a few dollars for their sponsors.”

Ski activists also face another, less direct obstacle: Skiing isn’t always green. For high school and college skiers, races often mean long drives, especially when teams must make the trek to resorts that can make their own snow. Plane rides to World Cup races and water-based snowmaking make for a sport that isn’t always environmentally friendly.

“Cutting carbon footprint is something people try to pay attention to, but it’s also something that I haven’t seen that active of an effort for in the ski community,” former Bowdoin skier Sam Shaheen said. “We’re a sport whose fate is tied to climate change, but we’re also dependent upon carbon.”

Greylock senior captain Miriam Bakija noted that skiers may have a hand in climate change while bearing much less of its consequences than others.

“It’s a bummer that we can’t ski,” Bakija said. “But it’s going to be a bigger bummer as more and more people in developing countries die because of the climate crisis.”

Shaheen brought up another element of skiers’ role in the environment, frequently discussed quietly–the long, carbon-backboned molecules stretched out by as many as eight Fluorine atoms. Or, in less, chemical terms, the fluoros.

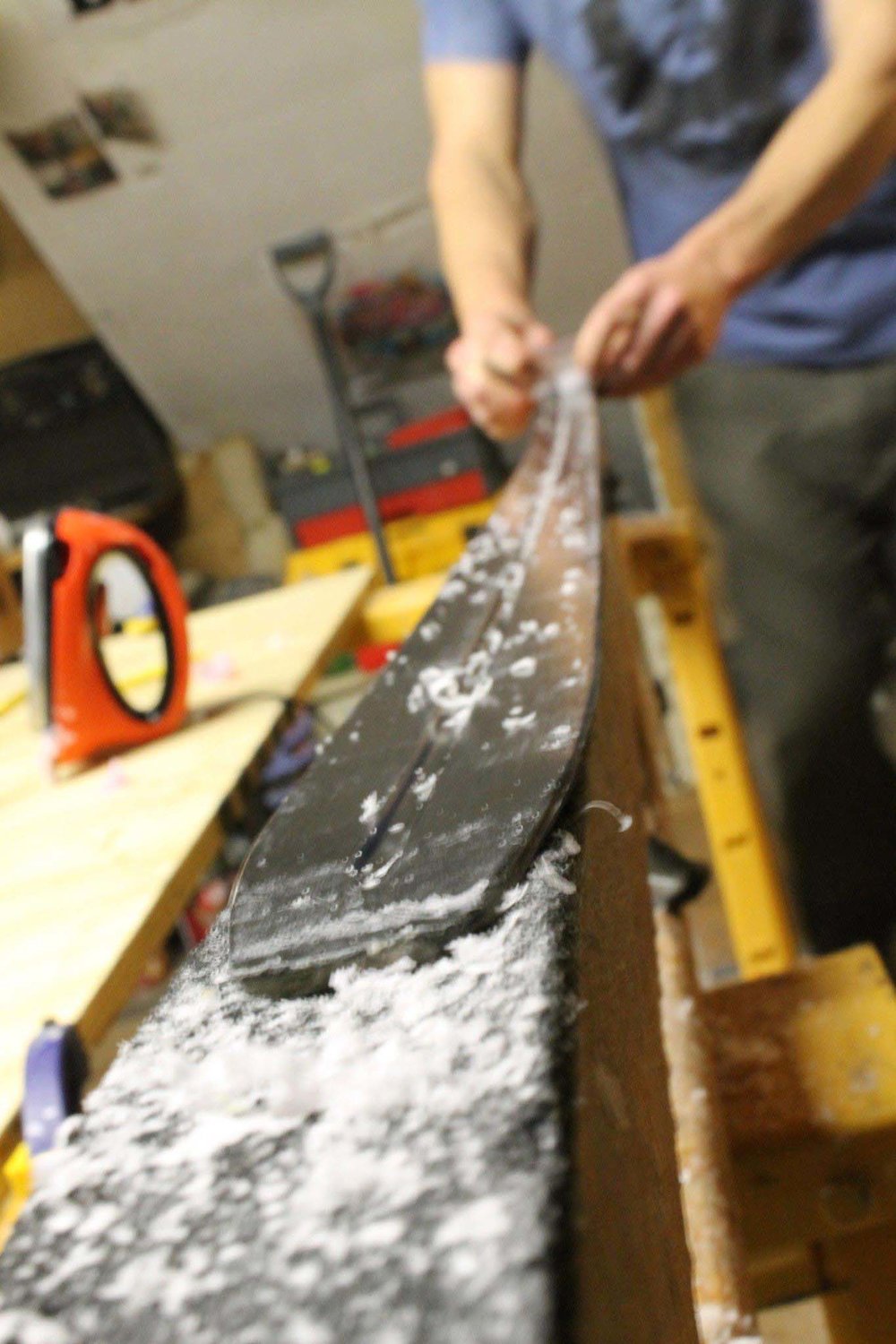

Waxed On, Never Waxed Off

Nearly a decade ago, a team of Swedish researchers at Orebro University tracked eight world cup wax technicians’ blood levels of Perfluorooctanoic acid (or PFOA — a chemical found in some of the fastest ski waxes). An unexposed, or control, group was found to have on average 2.7 nanograms of PFOA per milligram of blood. The wax techs boasted a number over 40 times larger–112.

Just this month, another group of Swedish scientists identified eleven waxes still containing significant levels of PFOA. Researchers involved said the wax manufacturers had claimed that they had moved on from PFOAs, but the waxes tested contained up to 1,200 times the amount of PFOA allowed under a new threshold set to take effect this summer.

In a 2019 report, Food and Water Watch said that “these chemicals are forever,” referring to PFOAs and similar substances. The acid stays in the environment, and doesn’t leave.

“These substances continue to persist in the environment and in our bodies even after a partial phase-out of their production in the United States,” the report read. “They’re resistant to even the most advanced water treatment technologies.”

Fluorinated waxes–a broader category, the fastest of which include PFOA–have endured criticism from coaches, scientists, and officials for years, especially for their health and environmental footprints. Bloomberg’s Will Donahue wrote of the sport’s “Dirty Little Fluorinated Secret,” describing fluoros as an addiction. The EPA has been investigating the substances, and has categorized the waxes as in violation with US toxic chemical legislation. Leagues across the world have set bans.

Vermont has set a ban, said Greene. So has New York. So has the Massachusetts state team qualifier. The European Union is banning the import, sale, and production of PFOAs in 2020 and fluorocarbons, the acid’s close sibling, two years later.

Early this winter, the International Ski Federation (FIS) announced a ban on the waxes for competitions starting in the 2020-2021 season.

And 41 days after the pros voted to de-fluorinate, the Berkshire Nordic Ski League followed suit.

“It seemed to us like a no-brainer,” Greene said. “Why would we ever continue to use it?”

Greene said once league coaches started hearing about the bans in Europe and gained access to more information regarding environmental and health concerns of fluorinated waxes, they met to discuss. Greene and fellow Greylock coach Hiram Greene pushed for a Berkshire League ban.

“Coach [Hiram] Greene said that even if the league doesn’t ban them, Mt. Greylock’s not using them,” Greene said.

Also at the meeting was Bazzano, who said the ban was a frantic decision.

“I was the antagonist,” Bazzano said. “The decision was made quickly. I feel that it was made without all the facts. It was more like ‘it’s a good idea, let’s just do it.’ I just didn’t feel like that was a decision to make that quickly.”

Bazzano said he questioned some of the information used to decide.

“In Norway, only U16 is using fluoro,” he said. “Everybody above U16 is using fluoro. That’s kind of information we got afterwards. We’ve been using Low Fluoros for 30 years. We just didn’t see health issues right away; we didn’t see it as an issue. Health issues have been reported for wax techs on the world tour, but I think they’re in a different element than we are.”

“In my mind, that was ridiculous,” Greene said, referring to such dissent at the meeting. “We don’t know everything, we’re still learning about them. Just inhaling the particulates is really bad for people.”

Greene said concern over the ban also originated from financial reasons–that a coach had already bought fluorinated waxes for the season.

Senior captain Miriam Bakija said that avoiding the ban for financial reasons would be “really stupid.”

“In the long run, regardless of whether you’ve bought them already, everybody’s going to be saving money by not using these super expensive fluorinated waxes,” she said.

Green noted that eliminating fluorinated waxes can level the playing field financially.

“It should be a concern,” she said, “because it shouldn’t be that the skiers with the most money get to be the fastest on skis.”

“Some people and teams can’t afford to buy fluorinated waxes,” Bakija said. “And in a sport in which so much of your race depends on the equipment you have, it’s nice to level the playing field in some way.”

In the end, the league voted to ban the use of all fluorinated products from racing. According to the new rules, skiers must wax as a team with NF (non-fluoro) and their skis must be stored overnight in a consolidated location.

Fifty percent of respondents to the Echo’s survey said they strongly supported the league’s ban on fluorinated waxes. Only one respondent reported they strongly disapproved of the decision. Reasoning largely captured the sentiment of the coaches who voted on the ban.

“If there are ways to help the environment then we should support that,” one respondent said. “Communities all over should do their best to not contribute to the climate crisis,” another noted.

Skiers also appeared to be concerned about the health impact, saying that “it is good to lower risky health factors” and noting that “without proper ventilation kids can be exposed to toxic fumes.”

But other skiers noted the complexity of the situation.

“I definitely support the decision, but it does raise some issues in the sport,” one said. “It makes it far easier to cheat the system now by using the better wax that has been banned because there is no way to actually regulate what people are putting on their skis.”

Looking Forward

Bakija said she is expecting the ski community to do more in the future to reduce skiers’ environmental footprint and keep the sport safe.

“We’re going in the right direction in terms of banning fluorinated waxes,” she said, “but there are definitely more steps. Do World Cup skiers need fifteen pairs of skis? Not really. Do we really need even CH waxes? Probably not. As long as the playing field is level, it’s still going to be a good sport. You don’t lose what’s great about skiing when you lose the waxes.”

Survey respondents shared similar sentiments, noting that they “really have never seen that great of a difference,” and therefore that there’s no reason not to move forward with the bans.

Beyond waxes, Newell said the ski community should do several things to ensure a future for the sport. Less infrastructure should be built, and large events like the upcoming Beijing Olympics should move toward carbon-neutrality, he said.

But he’s also looking to see a change in the culture of the sport.

“We need to breathe some new blood into these organizations,” he said. “There’s going to be an insurgence of younger athletes who are much more socially conscious and mentally conscious than the ones before them. I have no doubt that the changes will happen over time.”

Greene said she hopes skiers at the high school and professional level will set good examples.

“When you reach the highest level of your sport, you have a responsibility to be a role model and activist,” she said. “We don’t just want good skiers. We want good people.”