How Much Do You Think I Like You? A Look at Social Media Trends

There’s been something happening on Instagram that has become a fairly regular sight — and yet it is anything but normal.

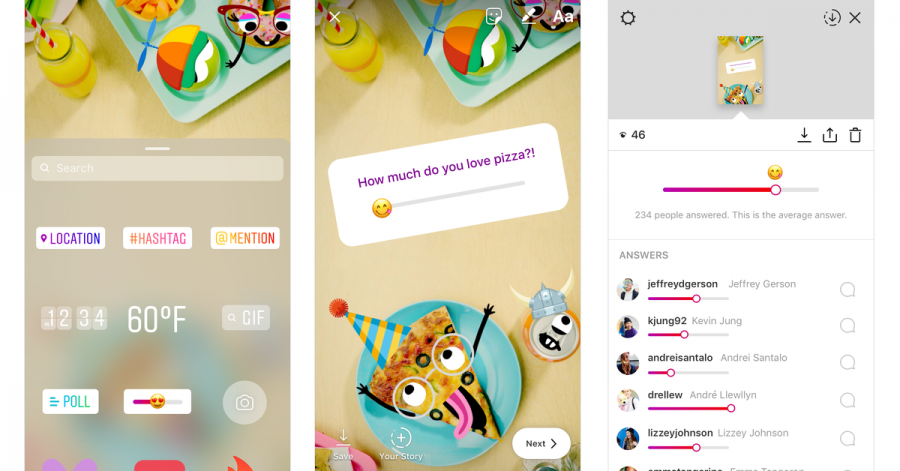

Ever since Instagram released new features for their stories, people (almost all between the age of 12-18) have been playing a sort of game with them. Instagram offers question boxes and polls that people can put on their stories — a story, for the non-Instagram users, is a temporary picture that can be posted to one’s profile for exactly 24 hours — as they see fit. For example, one might ask their followers if they like strawberry or raspberry jelly and the poster can see the results of the poll and who voted for what. Another feature is an answer slider that follows a question. I could hypothetically ask my followers how much they like strawberry jelly and they could slide depending on how much they enjoy it – a little bit of “slide” meaning they like it a bit, and a full “slide” meaning they like it a lot.

The problem, however, is that people are doing this with other humans. A popular “story game” is to ask one’s followers “How much do you think I like you?” The follower then slides depending on how much they believe the person posting likes them.

This is weird enough — but then the poster screenshots the responses and posts them to their story for all of their followers to see and corrects them. So if I had thought a person liked me as much as possible, they could mark wherever they wanted (either more than I thought, or less), essentially telling the person publicly how much they like them. They often add little comments or even the common “idk u,” where they don’t correct the person at all.

As senior and Instagram user Cathy McPartland puts it, “the ‘how much do I like you thing’ is so damaging to self-esteem. There’s no reason to do it unless you’re being nice. I see mostly girls doing it, and teen girls are already especially at risk for having low self-esteem.”

She explained, too, that it can be tempting to fill it out: “it’s all so bating because you want to know people’s opinions of you, but there’s really no reason to know that stuff. Just be civil.”

Social media has been a host of “games” like this for quite some time. Since the use of Snapchat and Facebook became popular among teens, “TBH and rates” were given when requested by people offering to do them. This “how much do you think I like you” game is similar, but worse — it is not private.

Another social media trend has been the popularization of Snapchat streaks. A streak occurs when you have “snapped” a person for more than three days in a row and you can continue it for as long as you want, as long as both users are sending a Snapchat every day. However, some people have streaks without even saying anything to each other (I know I’m guilty), just for the purpose of keeping it. McPartland commented on this habit as well: “streaks are good if I talk to you every day and want to talk you, but it’s this weird compulsion when people feel like they have to keep them going. It’s like fake friendship. But it’s a genius business model; Snapchat is tricking you into using their platform more.”

Now a senior, Sage Bohl has seen the rise and fall of several of these apps and games. She explained that while anonymity may offer some more privacy between users, “it can always be used in a bad way because there are no consequences.”

During junior year, senior Connor Daley took a brief break from the world of iPhones and used a flip phone. His primary reason was to disconnect from social media. “When I started using my flip phone,” he said, “I didn’t feel left out at all because I was still able to be reached by everyone.” However, he soon came across some simpler technicalities. “My phone just had poker on it and I would play that. And all the time I spent on Instagram was just used to send a text to people because the keyboard is weird.”

On his reason for leaving social media, Daley told the Echo that he “would always see those things on social media that were like, ‘what do you think of me, rate me out of 10, tbh?’” His response was “no sir, count me out.”

Social media is complex, widespread, and relatively new. What is certain is that teenagers, when exploring these phenomena, are wading in unknown waters. “How Much Do I Like You” and similar trends have risen. Whether or not (or when) they fall, only time may tell.